Professor Barbara Creed on Feminist New Wave Cinema and the evolution of horror

Professor Barbara Creed is a cinema studies expert and author of seven books, including The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. For our SCI-FI zine, Creed wrote about Feminist New Wave Cinema and filmmakers from around the world changing the genre of horror.

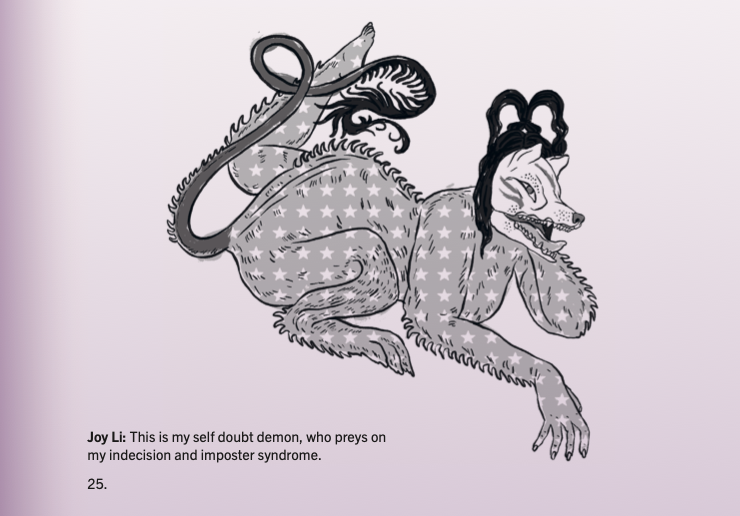

Illustration by Joy Li for SCI-FI zine

The Monstrous-Feminine in the Science Lab

Vampire, woman-wolf, ghost, demon, lesbian mermaid, terrorist, cannibal––these are some of the faces of the monstrous-feminine of contemporary horror and science fiction films. All human societies have a concept of the monstrous-feminine from Medusa, Circe and Medea to contemporary versions of the monstrous mother, alien, and castrating avenger. Who is the monstrous feminine, the human and nonhuman creature, whose presence permeates a range of practices – film, art, sculpture and literature? Why is there such an interest in her image – her mythical heritage, terrifying faces and supernatural powers? I argue (2022) that this interest, which has been sparked globally in the twenty-first century, is a response to social and economic change, and the emergence of social protest movements such as new wave feminism, women’s equality, the LGBTQIA movement, de-colonialist debates, race, and the destruction of the planet as evidenced by global warming and the extinction of species. Directors create new images of monstrousness, experimenting with forms and shapes in order to bring the abject – a blurring of boundaries – to life.

The monstrous-feminine appears in a range of films globally, all of which address these issues: the Australian film The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent 2018) investigates colonial violence, racism and rape; the Polish film Spoor (Agnieszka Holland, 2017) focusses on the sexual exploitation of women and cruelty to animals; the Japanese Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998) presents the monstrous female ghost as a victim of male violence; while Raw (Julia Ducournau, 2016) from France examines male aggression and the failure of the patriarchal symbolic order. In the above films, the monstrous-feminine adopts very different faces: a young convict woman; a menopausal witch; a frightening ghost; and a female cannibal. In each film she embarks on a personal, intimate journey into the dark night of abjection where she confronts her own inner need for change and the (almost always) male monsters who see her as an enemy of the patriarchal symbolic order.

In the new millennium, female film makers (and some male directors) have turned to myth, horror and science fiction to explore stories of women who assume the mantle of the monstrous-feminine in order to rise up against their oppression and fight back. The monstrous feminine of modern myth is essentially a terrorist. I argue (2022) that their films form a new historical phenomenon – Feminist New Wave Cinema. New wave directors represent a range of ethnicities and countries. They speak in their own voices, experiment with narrative, and create new, controversial films. The new generation of film makers who work in horror and science fiction break with the classic horror tradition, adopting new aesthetic and experimental forms. Their films have won international awards, and critical recognition. Revolt is central to the monstrous-feminine, not only external but also inner, intimate revolt. Julia Kristeva sees intimate revolt, as distinct from large-scale social revolution (or male-inspired revolt) which she argues has failed to usher in social, economic and political change. She regards intimate revolt as crucially important – particularly for women. Intimate revolt represents small, personal actions which are ‘necessary to preserve the life of the mind and the species’. (Kristeva, 2002. p. 5)

“‘Monstrosity, for me, is always positive. It’s about debunking all the normative ways of society and social life’. ”

Monstrosity is an empowering concept in Feminist New Wave Cinema. New wave directors explore the meaning of the monster, of monstrosity, and its power to challenge dominant male mores and oppressive social structures. Julia Ducournau who directed Titane, which won the coveted Palme d’Or at Cannes, says: ‘Monstrosity, for me, is always positive. It’s about debunking all the normative ways of society and social life’. (2021a) New Wave films about the monstrous-feminine include directors such as Patty Jenkins (Monster, 2003), Karyn Kusama (Jennifer’s Body, 2009), Ana Lily Amirpour (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014), Jennifer Kent (The Babadook, 2014), Ísold Uggadóttir (And Breathe Normally, 2018), Emerald Fennell (Promising Young Woman, 2020), Chloé Zhao (Nomadland, 2020) and Julia Ducournau (Titane, 2021). The monstrous-feminine is often monstrous in appearance but also monstrous because she undermines the patriarchal order, and experiments with life and its many choices. She is a threat to law and order and the subjugation of women and other oppressed groups.

Most Feminist New Wave films utilise the conventions of the horror film to convey the reality – often the surreality – of the human struggle. These films, however, are not classic scream-queen horror films, but instead explore the horrific via different genres, including horror, science fiction, environmental tales, the woman’s story, rape-revolt and social issue films. Holland has said Spoor is a revenge story which she was drawn to because its genre boundaries are permeable giving her flexibility to explore her argument.

You cannot really tell if it is a thriller, a dark comedy, some kind of ecological manifesto, an artistic drama, or perhaps a fairy tale. It’s a mix of reality and fantasy, and the main character is some kind of witch from my generation who just cannot accept the cruelty and the injustice of this male-driven hunting chorus. And of course hunters are not the only people who actually kill animals, but they are also the metaphor for the brutal power that doesn’t have any kind of empathy or interest in the lives and feelings of the weakest. (Holland, 2018)

Illustration by Joy Li for SCI-FI zine

Their narratives focus on women in revolt against male violence and corrosive patriarchal tenets including misogyny, racism, homophobia, and anthropocentrism. On a journey to discover their own identity and desires, the protagonists –through the guise of the monstrous-feminine – embark on a personal journey into the dark night of abjection, where they engage with the underlying horrors of the patriarchal order, emerging changed in fundamental ways. In so doing they experience – live through – a state of abjection: crossing borders, undermining boundaries, embracing formlessness. Patriarchal ideology defines the monstrous-feminine as abject because she does not respect borders.

It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite. (Kristeva, 1982, p. 4)

Because of her reproductive nature she signifies ‘leakiness’. The monstrous-feminine of new wave horror embraces abjection through her disrespect for borders and boundaries. She draws on her menstrual, reproductive and birth-giving powers to speak in her own voice and assert her own desires.

In abjection, revolt is completely within being. Within the being of language… the subject of abjection is eminently productive of culture. (Kristeva, 1982, p. 45)

I argue that when the monstrous-feminine in her revolt enters into the dark night of abjection she creates –through her erosion of boundaries – a form or experience of ‘radical abjection’, a new language of the personal and intimate, a new form of myth. (Creed 2024, 189-200) In discussing her controversial award-winning film, Titane, in which the female protagonist, a mother in revolt, gives birth to a car-baby, Julia Ducournau says that we need new myths for the present age.

I wanted to create a new world that was the equivalent of the birth of the Titans after Uranus and Gaia mated. The sky and the earth. That’s where it came from. (2021 b)

A number of contemporary films present a new narrative in which a female Frankenstein creates new life-forms. She signifies an uncanny matrix or womb. The monstrous-feminine as uncanny creatrix is central to Splice (2009), Evolution (2015), Border (2018), Little Joe (2019) and Titane (2021). Bella, the heroine of the recent award-winning Poor Things (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2023), overpowers her husband, who is planning to give her a clitoridectomy, and re-creates him as a goat in her own version of the Garden of Eden. Played by Emma Stone, Bella is ‘created’ by Godwin Baxter, a Frankensteinian figure who reanimates the body of a pregnant suicide victim with the brain of her unborn foetus. When Bella takes on the role of a female Frankenstein she gives man a goat’s brain.

“Played by Emma Stone, Bella is ‘created’ by Godwin Baxter, a Frankensteinian figure who reanimates the body of a pregnant suicide victim with the brain of her unborn foetus. When Bella takes on the role of a female Frankenstein she gives man a goat’s brain.”

Illustration by Joy Li for SCI-FI zine

Ducournau compares the heroine of Titane to Mary Shelley’s monster (235) but from an ironical perspective. ‘The less she looks human, the more she gets in touch with her own humanity’ (2021 c) In discussing Little Joe, Jessica Hausner, who creates a happiness plant in her science lab, states:

The idea was to do a female Frankenstein story. A female scientist who loves her work, who creates something that then takes on a life of its own. But with a different ending, a more ironic, forgiving end, where the monster and its creator don’t have to destroy each other. (2019)

Possibly the most ancient face of the monstrous-feminine is the monstrous-mother. While in classic male-directed horror of the 1970s and 1980s woman was represented as monstrous because of her abject sexual, reproductive and birth-giving powers (Carrie, The Brood), in feminist new wave sci-fi horror she is monstrous and marvellous because of her generative womb –– her inner science laboratory. She is the uncanny creatrix harbouring or giving birth to often surreal and bizarre life-forms as in Prevenge (Alice Lowe, 2016), Splice (Vincenzo Natali, 2009), Border (Ali Abassi, 2018), Little Joe (Jessica Hausner, 2019) and Titane (Julia Ducournau, 2021). The alien femme fatale of Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013), played by Scarlett Johansson, symbolically takes back the life she once birthed. She seduces her male victims, leading them to the inky black waters of her death pool – a bottomless womb – where she eviscerates them in surreal scenes in which they almost instantly are transformed into packages of meat to be eaten on an alien planet far, far away. Kjerstin Johnson voices a popular response to the alien femme fatale who decides to relinquish her alien identity to become human. She found her transformation into an ordinary woman as ‘uncomfortably familiar’. When the alien used her supernatural powers, however, to seduce lone men at night and lure them into her deadly waters, Johnson responded to her as ‘deliciously powerful’. The monstrous-feminine might horrify the spectator but she also invokes surreal unexpected pleasures

References

Creed, Barbara. 2022. Return of the Monstrous-Feminine: Feminist New Wave Cinema. London and New York, Routledge.

Creed, Barbara, 2024. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London and New York: Routledge.

Ducournau, Julia. (2021a) ‘Palme d’Or Winner Julia Ducournau on Groundbreaking “Titane”: “I Don’t Want My Gender to Define Me.”’ Interview by Eric Kohn. IndieWire, July 17, 2021. https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/palme-d-winner-julia-ducournau-203739842.html?

Ducournau, Julia (2021b) ‘Titane.’ Interview by Eric Kohn. IndieWire, July 17, 2021. https://www.indiewire.com/2021/07/julia-ducournau-interview-palme-dor-titane-1234652010/

Ducournau, Julia (2021c) ‘Interview: Julia Ducournau on Building Her Own Modern Mythology with Titane.’ Interview by Marshall Shaffer, Slant, September 30, 2021. https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/julia-ducournau-interview-titane/

Hausner, Jessica (2019) ‘Mumbai: Jessica Hausner on Directing Her “Female Frankenstein Story.”’ Interview by Scott Roxborough. The Hollywood Reporter, May 17, 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/jessica-hausner-directing-her-female-frankenstein-story-1211777/

Holland, Agnieszka. 2018. ‘An Interview with Spoor Director Agnieszka Holland.’ Interview by Cynthia Biret. Riot Material, January 16, 2018. https://www.riotmaterial.com/interview-with-spoor-director-agnieszka-holland/.

Kristeva, Julia. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kristeva, Julia. 2002. Intimate Revolt: The Powers and Limits of Psychoanalysis. Translated by Jeanine Herman. Vol. 2. New York: Columbia University Press.

This essay first appeared in the SCI-FI: Mythologies Transformed exhibition zine.