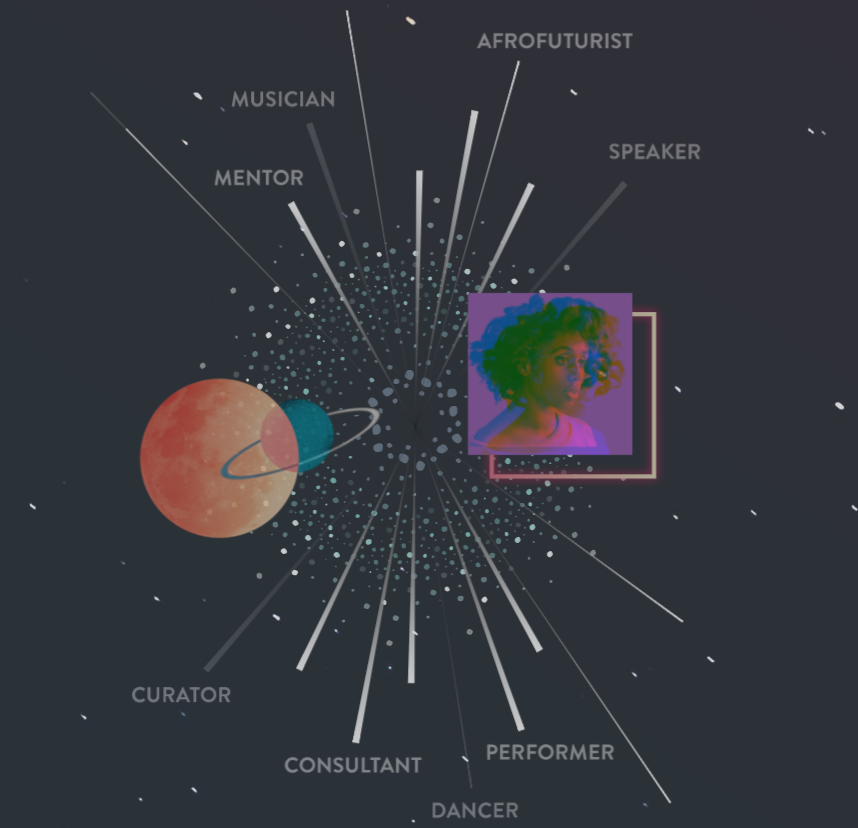

Meet the Artists Behind MENTAL: Nwando Ebizie

Nwando Ebizie is a multi-hyphenated creator who invites audiences into her perceptual world, meeting them at the intersection of mythology, dreams and lucid worlds through the lens of black culture and history. Her work tenderly prompts audiences to question their underlying biases and subjective understanding of a shared reality. As documented by the immersive exhibit Distorted Constellations, Nwando’s reality is influenced by living in a world frosted by Visual Snow, a rare neurological condition characterised by flickering static-like spots, auras and glowing lines that occupy her visual field.

Distorted Constellations is on display as part of Science Gallery Melbourne’s latest exhibition MENTAL: Head Inside.

Photo by Dimitri Djuric

Hello Nwando, can you tell us a bit about your background and how you got into art?

I think very early on. As a child, I remember feeling a very strong physical sensation that I describe as a bit like electricity. I interpret it now as a need to express things.

I think many creative people feel things physiologically and need an outlet to externalise their ideas or emotions.

Yeah. I wonder what happens to other people. Does that leave for other people because they just find more ‘socially normal’ means of expression, like language?

I have two sisters. One of them is a major normie and the other identifies as a witch. It’s interesting to see how people externalise their electricity. I think ‘socially normal’ people channel it into sports or dating or something. It comes out somewhere.

It has to come out somewhere, right? It’s part of our humanity as socialised beings to create harmony between our inner and outer worlds. I think that art (in all its forms) gave me access to that. It’s been quite a long journey. I started out in dance when I was a kid and theatre. And I’ve moved through performance art and now I’m working more and more in visual art and sound and music. I guess that’s because I don’t really feel limited in art and expression, so I don’t see why I would need to limit myself. I feel limited in the world and art is a place to let go of those kinds of boundaries. For me, the art form is not the important thing: it’s all just a paint box in which to work out what is the right colour for this particular idea. I think it’s very painful for people who don’t find the connection between their inner and outer worlds.

I’m interpreting it as dissociation. When your internal dimension doesn’t fully align with the one you’re seeing and experiencing firsthand.

I think that’s why I’m interested this idea of liminal states in my work. In new age spirituality especially, there’s a lot of interest in liminal states–those cross-over states and what can happen in them. I’m interested in art being a place where people can access these. I mean, we access them every single day when we go to sleep, but because we’re not conscious, it’s not so easy to explore. I love the concept that an artwork can give you access to these liminal states while awake. Accessibility is a big word for me, I keep coming back to it. The world is just so inaccessible and I think it’s seen as an additional add-on a lot of the time.

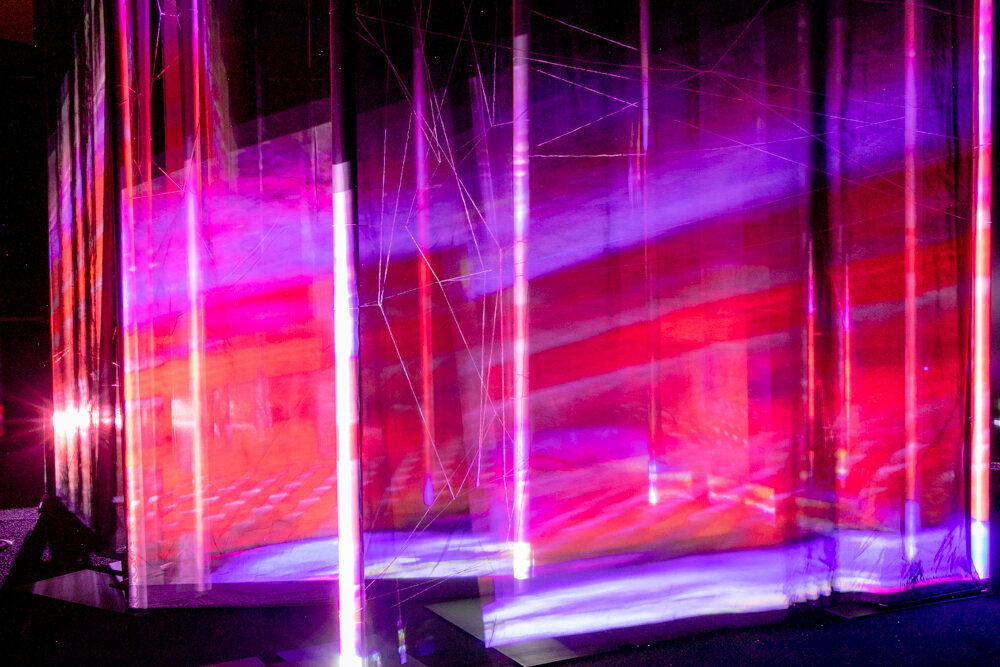

Installation view of Distorted Constellations by Nwando Ebizie (UK) in Science Gallery Melbourne's MENTAL, (Alan Weedon, 2021)

I think it comes back to the message behind your exhibit ‘Distorted Constellations’ which is that our subjective experience of the world is our reality. How do you think being neurodivergent informs your reality and art practice?

Learning about my neurodivergence has been a process of at least seven or eight years and it’s still ongoing. Learning and accepting my neurodivergence has completely changed my perspective on myself and it allowed me to let go (although not completely, it’s a work in progress) of ideas about myself that were keeping me constrained, that were keeping me super self-critical. ‘Why can’t you do this when other people find it so easy?’ Letting go of that idea of an objective shared reality. I mean, not completely… I still live in the world.

You’re still constrained by the expectations of living in the world, but you allowed yourself to let go of some of the self-imposed pressure. And now you have the language to back why something might be harder for you, and how you can make accommodations.

Going through all of that made it so much easier for me to create work. It really just started pouring out. And I hadn’t even realised I’d been holding it in. I feel like it’s so inherently, so intrinsically bound up by neurodivergence. What you put out into the world and what’s happening inside your world is deeply connected. I deeply enjoy understanding what my process is. It’s quite often constellation-like. There are lots of ideas and practices and inspirations and outer and inner, that in the end conjoin to make a product. But in the beginning, they feel very disparate. My realisation has been to allow it to make no sense, until it makes sense.

I think society really encourages us to be one-track-minded. It’s very freeing to let yourself move sideways, in every direction.

That’s exactly my process! Flowing on from that, I subscribe to the social model of disability which is kind of the idea that one is disabled by the society.

Is that the concept that there is nothing inherently wrong with the disabled individual, but it’s a failure on behalf of society to accommodate their needs?

Yes, and I really believe that. You internalise ableism because that’s the society around you. Unpacking that is one of the biggest works. The way that I push myself too hard. No one pushes me to ill health. It’s mostly me. With my workload, there is a constant burnout that happens. I’m trying really hard to not internalise the capitalist system we live in. But I also have to take responsibility for part of that. I’m an adult and I can control my reality, so what can I do to lessen that?

I follow a lot of millennial therapy accounts on Instagram. Something that came up recently was a post about feeling overwhelmed by making a sandwich for lunch. And this therapist said ‘Then don’t. Grab a handful of shredded cheese and a handful of cherry tomatoes. Deconstruct it’. It stuck with me because we hold ourselves to these arbitrary, invisible standards like ‘it has to look like a sandwich’. It’s this freeing thing to realise that it doesn’t.

That is a beautiful example. It’s a lot of work to unpack that. And to do the work of unpacking. There’s also this comfort in repeating things that are difficult because they’ve always been that way.

I think the pathways in the brain have been travelled down so many times that it becomes instinctual. Like you said, it takes a kind of invisible labour to change your thinking.

That’s the biggest bit, isn’t it? It’s very energy draining. But I don’t believe the idea that as an artist you have to push yourself to the extreme. I try and create art that allows space. That allows a mere of people to project their inner and outer world. If there’s intensity then there’s also a contrast of space. I try to build that into the process. I don’t have the separation of paid labour under capitalism and labour for oneself. It all needs to be healing. I’m interested in ritual process and healing and transformation.

Ritual feels like a huge pillar underpinning your practice.

I’m interested in ritual and my belief system holds that art and expression can be a way to connect people and to create inner (and potentially outer) change. The important thing is to find the right medium to give people access to themselves, to the world, to ideas and to potentially change their ideas.

Photo by Claire Shovelton

Distorted Constellations is a reflection of your experience living with the invisible condition, Visual Snow. How do you think society as a whole could be more inclusive and accommodating of people living with invisible conditions?

For myself, the concept of being neurodivergent I find to be more useful than saying I have Visual Snow. But there’s an added drain that comes from having a condition like Visual Snow which is very sensorially intense. I think it starts with education. We grow up and are educated with the idea that our brains are all the same. That we all experience the same shared reality. First of all, we have to undo that before people can even accept that there are invisible conditions, like perceptual differences. For instance, I was talking to a little kid recently and we were walking through a field, which sounds like such a made-up story...

You said it, not me.

We were walking across the moors on this beautiful day and he asked ‘does everyone see the sky so sparkly?’ And I said, ‘some people do. I do’.

I think every child goes through a phase where they begin to question ‘do we all see the colour blue the same way? What if the colour you’re seeing is something different but we’ve both just labelled it blue?’

Children are natural philosophers. They’re still very open. This kid hasn’t internalised yet that it’s not ‘normal’ for the sky to sparkle. A while later he was telling me about a kid in his class who he had labelled ‘crazy’ so I asked ‘what do you mean by crazy?’ and he said ‘no sorry, not crazy, mental!’ And I asked ‘what do you mean by mental?’ and he said ‘autistic’ and then ran out of language. He’s trying to piece together words he’s heard and he settled on crazy. Meanwhile, he made no connection that he sees a sparkly sky. It’s interesting that so early on, we’re separating off others.

Distinguishing them from some kind of unspoken norm.

Because it’s vital that we are in that norm. I think it probably starts from there.

I think as a kid, there’s a desperation to be like others. As you get older, individuality becomes more alluring.

Yeah, but there’s a certain level where difference becomes unacceptable. Continuing on from invisible conditions, our idea of ‘what is an acceptable human experience’ is way too narrow. And it’s also kind of juvenile and it’s very fixed. ‘If you’re this kind of person, you’ll be this kind of person for the rest of your life’. I think COVID has opened up many people’s eyes for the first time that situation has a massive impact on your ability. If you’re locked down and you feel that– yeah, you might begin to experience anxiety or depression. If you get COVID and then long COVID, you might find yourself becoming disabled when you weren’t before. Disability can ebb and flow, it’s not some fixed idea.

We all have the potential to face disability in our lifetime. It’s one of these labels that carries this real gravitas of longevity and... identity.

It becomes an identity! Too often, society only recognises physical impairment as disability. There is this lingering idea (in a hyper-capitalised society) that’s always trying to catch people out for faking. If you’re not some kind of visual indicator for your disability then you can get over it. To fight against that is so important. If that was deconstructed, the world would be better for everyone.

Something we’ve touched on throughout this conversation is how foundational our childhood and educational experiences are. I mean, school is the only time in a person’s life where you’re expected to be good at everything. In the real world, no one says ‘You’re an incredible artist and writer but gah, your Chinese-Mandarin is just not up to par’.

What would it look like to have access to knowledge but with the proviso that you don’t have to be good at it? How freeing. Why does there have to be grading? Yeah, education can be so powerful in shaping our understanding of ‘normal’.

I know you have to go so I’ll ask one last question. Alongside the augmented reality of pointillist dots, auras and glowing lines, Visual Snow can snowball into episodes of anxiety, depression, derealisation and depersonalisation. Is art a way for you to heal from these distressing elements? Is there anything else you do to support your mental wellbeing?

I live right by big hills in a little village in the north of England so I just go out. There’s a landscape here called the moors. It’s quite a bleak landscape but I love it. It’s quite boggy. There are places to go swimming, like little reservoirs and streams. Being active in nature. I have an instinctual need to move, to swim, to run.

It’s the electricity in your body. We’ve come full circle.

To see more from Nwando Ebizie visit nwandoebizie.com or follow @nwando_ebizie on Instagram.

This interview has been transcribed and condensed for clarity.